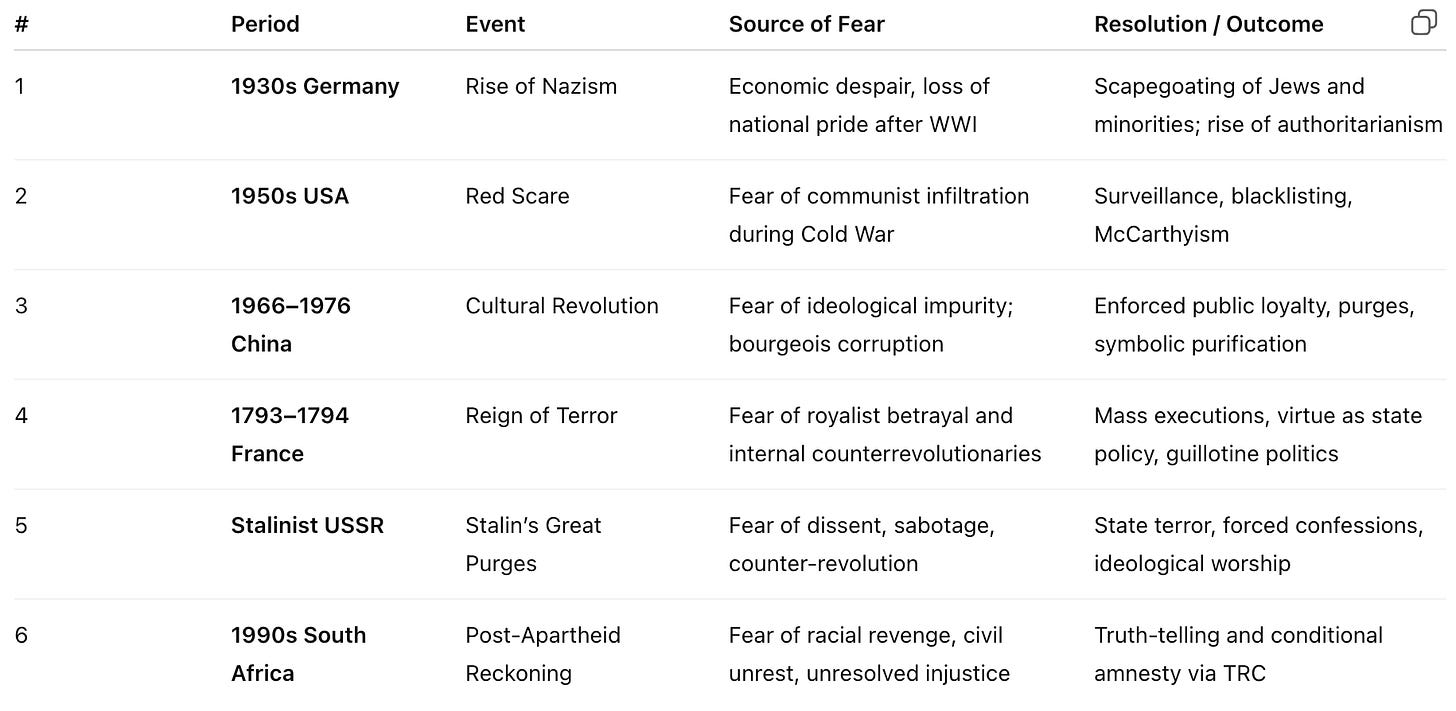

Below is a list of historical events marked by (among other things) an overarching fear. Your task? Choose the correct resolution based on the event and source of widespread fear. Think of it as "Fear of Injury: Global Edition." (answer key at the end, with some additional fear-based historical events & resolutions)

Each of these moments began with a fracture—an injury to the body politic, the psyche, or the soul. The kind of injury that, when ignored, metastasizes into fear, blame, and disconnection. The kind that tempts whole cultures to protect themselves at the cost of their humanity.

If you’ve read my previous essay on Fear of Injury, you’ll remember how personal injury—physical or emotional—can lead us to withdraw, self-protect, or hesitate in ways that seem wise but slowly separate us from joy. Now imagine this same pattern on a collective scale. The stakes grow. The fractures deepen. The fear spreads. This is not just personal anymore. This is global injury avoidance, and its symptoms are everywhere and very, very dangerous (but it doesn’t have to be that way, as I’ll show later).

So what happens when an entire society is afraid of injury, collapse, an “other”?

One consequence is what political theorist Hannah Arendt called "the shattering of the world as a shared experience." When fear infiltrates the collective psyche and remains unacknowledged, it fractures not just trust in institutions or one another—it fractures reality itself. What was once held in common becomes contested: truth becomes subjective, language loses its anchor, and the possibility of agreement disintegrates.

This is the condition Arendt warned against in her reflections on totalitarianism: not simply lies, but the systematic breakdown of a shared framework of meaning. In its place arises what scholars today refer to as post-truth authoritarianism—a climate in which facts no longer persuade, and emotional allegiance takes precedence over evidence. It’s not merely that truth is denied—it’s that its relevance is dismissed altogether.

Collective fear of injury paves the way for this breakdown. If reality itself becomes too painful or uncertain to inhabit, people will reach for the comfort of alternate narratives, even if those narratives are destructive. They will mistake coherence for truth and retreat into echo chambers that affirm their fears rather than confront them.

In this sense, the fear of injury—when writ large—becomes not just a private avoidance but a cultural collapse in how we know what is real.

America as a Psyche in Crisis: Shadow Inflation

Carl Jung believed that what we repress as individuals—and especially as societies—doesn’t simply vanish. It gathers force. When left unintegrated, the shadow doesn’t disappear; it projects outward. We see enemies where we haven’t acknowledged our own complicity. We moralize our rage instead of metabolizing our grief. We polarize.

In Jungian terms, America is deep in the throes of shadow possession. The unconscious is erupting into public life—not as insight, but as reaction. Not as healing, but hysteria.

It’s not hard to see where this comes from. We’ve never fully reckoned with our national wounds: the legacy of slavery, the genocide of Indigenous peoples, the trauma of endless war, our reliance on extraction—of labor, of land, of life. We’ve mythologized ourselves into a kind of moral immunity, telling stories of liberty and exceptionalism while side-stepping the shadow.

But the shadow doesn’t wait politely to be acknowledged. It appears in projection—onto immigrants, onto “the other side,” onto institutions once thought sacred. When we don’t integrate our fear, we outsource it. And when enough people do that at scale, the entire public psyche becomes governed not by wisdom, but by reflex.

We’ve seen this before. In 1930s Germany, widespread fear, humiliation, and economic despair created fertile ground for scapegoating and collective shadow projection. Hitler’s rise wasn’t just about political ideology; it was about a people who had lost their symbolic center and were willing to trade it for certainty. The result was a catastrophe. The fear wasn’t healed, it was weaponized.

Or take the Red Scare in the U.S.—a time when fear of infiltration replaced trust in our neighbors. This wasn’t integration. It was overcorrection. A shadow reaction dressed in patriotic clothing.

Today, the fear landscape is even more saturated. According to the Chapman University Survey of American Fears, the top ten fears in 2024 all surpassed 50% of the population. These fears include corrupt government officials, economic collapse, loved ones dying, and threats of war or terrorism. Unlike past decades, these fears are not isolated to specific groups or regions—they are nearly universal, ambient. Fear is no longer episodic; it has become environmental.

Neuroscientific studies deepen this picture. Recent research reveals that individuals process and generalize fear in markedly different ways—some through sensory exploration, others through memory-based reinforcement. In both cases, fear becomes more persistent when the brain lacks contextual anchors. Without grounding, our threat response generalizes. Everything becomes suspect. Everyone becomes a potential enemy.

This may help explain why fear today feels so inescapable. We lack shared rituals or stable symbols to metabolize threat. Instead, our neural pathways are flooded by algorithmic stimuli and unresolved memory. The very structure of our digital lives reinforces a constant readiness for conflict, a posture of vigilance rather than reflection.

The Collapse of Shared Symbols

Jung taught that every culture depends on shared symbols—images, stories, myths—that offer orientation. Without them, we lose our north star. We reach for conspiracy or collapse.

In the United States, the traditional unifying myths are fraying. "The American Dream" feels increasingly inaccessible. Manifest Destiny has long since soured. Christian nationalism, which once wove faith and identity into a singular myth of chosenness, now fuels division. The symbols that once promised wholeness have become sites of conflict.

In their place: misinformation, tribalism, cynicism, and retreat. We create personality cults. We mistake extremity for authenticity. We cling to purity politics and online liturgies of outrage. We want meaning, but lack ritual. We want belonging, but substitute it with algorithmic affirmation.

In this vacuum, new forms of control emerge. Maoist China, for example, saw the obliteration of shared cultural history as a tool of regime power. The Cultural Revolution filled the symbolic void with enforced allegiance, public humiliation, and violent purification. It wasn’t just ideological, it was mythological. It replaced meaning with spectacle.

America is not immune. When shared symbols collapse, fear rushes in to fill the void. And that fear becomes policy.

Mass Consciousness vs. Individuation

Jung was deeply skeptical of mass movements that dissolved the individual psyche. He saw the collective as important, but warned: when we merge into groupthink, we abandon the sacred labor of becoming whole.

Social media has accelerated this crisis. We don’t reflect; we react. We don’t ask what’s true, we ask what will resonate. We become archetypes: the victim, the savior, the villain. And once you’ve been cast in the wrong one, there’s no path to reintegration—only exile.

This flattening of the self into spectacle is not new. During the French Revolution, mass paranoia led to the Reign of Terror. Neighbors turned on neighbors. Virtue became a weapon. The individual disappeared into the cause, and when the cause shifted, so did the guillotine’s blade. There was no room for nuance. No room for soul.

Jung might say we’re doing the same digitally. When we outsource our inner gaze to the crowd, we stop discerning. When we seek resonance before reflection, we become noise.

When Archetypes Break Through

Jung taught that cultural upheaval often signals the eruption of archetypes—timeless patterns that shape the psyche. When unacknowledged, they overwhelm the individual and infect the collective.

Today, the Trickster dances in our media and politics. The Warrior emerges in protest and polarization. The Wounded Healer shows up in trauma discourse. The Apocalypse whispers through climate dread, political decay, and AI panic. These aren’t inherently destructive, but when lived unconsciously, they distort.

Think of Stalin’s Soviet Union. The Savior archetype possessed the state—Stalin as father, seer, protector. But it came at the cost of millions of lives. Fear was ritualized into surveillance. Archetypes became dogma.

In our age, the archetypes are overflowing. They aren’t embodied, they’re performed. We mimic their posture but forget their purpose. They become memes instead of mysteries.

Jung would caution: we are not called to discard the archetypes, but to hold them with reverence. To live them consciously. To let them guide, not govern.

The Possibility of Renewal

But this isn’t all collapse. Jung never despaired of the shadow. He saw it as the birthplace of transformation.

A new myth can emerge—not from nostalgia or denial, but from reimagining.

We can root the American Dream not in consumption, but in communion. We can replace triumphalism with tenderness. We can teach emotional and psychological literacy as civic education. We can create art, liturgy, and leadership that doesn’t just signal virtue, but integrates shadow.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is one such example. It wasn’t perfect, but it modeled what it looks like to tell the truth at scale, to confess publicly, and to begin the long road of collective repair.

After the fall of apartheid, South Africa stood at a crossroads: revenge or reconciliation, denial or truth. The TRC chose the latter. Led by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and backed by Nelson Mandela’s vision, the Commission invited victims of state violence to testify—often on live television—about the atrocities they had endured. These stories were raw, often agonizing, but the act of public confession created a sacred space for witnessing.

Unlike traditional courts, the TRC offered conditional amnesty—not to erase justice, but to compel full disclosure. Perpetrators had to name their crimes in detail before the nation to receive pardon. Truth became the prerequisite for mercy. This was not about establishing moral innocence—it was about creating the conditions for moral clarity.

Jung might say the TRC was an act of collective shadow integration: the country did not bury its shame but exposed it to the light. The process allowed for complexity, acknowledging that some perpetrators were ordinary citizens, and that healing required confronting both what was done and what was allowed.

It wasn’t flawless. Reparations lagged. Economic disparities remained entrenched. Many victims felt abandoned by the lack of material justice. But even with its limits, the TRC modeled a rare ritual of public reckoning—one that replaced silence with speech, denial with naming, and vengeance with witness.

Its lesson for us is clear: truth must be spoken aloud. Pain must be held communally. And healing—while never linear—can begin the moment we choose to look at what has been hidden, together.

The point isn’t perfection. It’s integration.

And integration begins within.

We don’t need to wait for institutions to change. We can ask ourselves:

Where am I projecting instead of processing?

Where am I choosing purity over participation?

Who have I exiled in my own story?

The collective heals when the individual becomes conscious.

Jung would remind us: the soul doesn’t need safety. It needs truth. Jesus taught something similar. He never promised comfort. He promised presence.

The way forward is not spectacle. It’s sacrament. Not performance. But wholeness.

🤫Answer Key

Footnotes

Jung, Carl. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press, 1969.

Chapman University Survey of American Fears (2024).

https://www.chapman.edu/wilkinson/research-centers/babbie-center/survey-american-fears.aspxThe Guardian. “Top 10 Fears of Americans in 2024 Revealed.” The Guardian, October 29, 2024.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/oct/29/top-ten-american-fearsLeDoux, Joseph. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster, 1996.

PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences). “The Role of Context in Human Perception of Fear.” April 2024.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2414677122Nature Mental Health. “Two Modes of Fear Generalization in Humans.” January 2024.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-024-00287-xCold Spring Harbor Laboratory. “How the Brain Processes Fear.” August 2020.

https://www.cshl.edu/how-does-the-brain-process-fear/Desmond Tutu and the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. No Future Without Forgiveness. Image Books, 1999.

Sarkin, Jeremy. Carrots and Sticks: The TRC and the South African Amnesty Process. Intersentia, 2004.

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt, 1951.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019.